Panel: Coming Soon – The Future Of Gene Editing And Gene Therapies

Farah Qaiser recently completed a Master of Science at the University of Toronto, where she carried out DNA sequencing to better understand complex neurological disorders. When not in the lab, Farah enjoys writing about science and scientists for various media outlets and is one of the co-founders of the Toronto Science Policy Network.

In December 2020, the Gairdner Foundation, the Council Of Canadian Academies (CCA), the Krembil Foundation and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute partnered to host Breaking Through: Delivering On The Promise Of Gene Therapy, a two-day long 2020 Gairdner Ontario International Symposium about gene therapy research and practice.

This symposium explored different aspects related to the recently published CCA report, titled From Research to Reality. In this report, the Expert Panel on the Approval and Use of Somatic Gene Therapies in Canada assessed existing evidence to describe the steps, barriers and challenges involved in the approval and use of gene therapies in Canada. The symposium’s closing panel discussion, titled Coming Soon – The Future Of Gene Editing And Gene Therapies, explored the future of gene therapies and gene editing. To date, there are very few gene therapies which have been approved for use in Canada, including Novartis’ Kymriah and Zolgensma, Gilead’s Yescarta and Biogen’s Spinraza, making this discussion a very timely one.

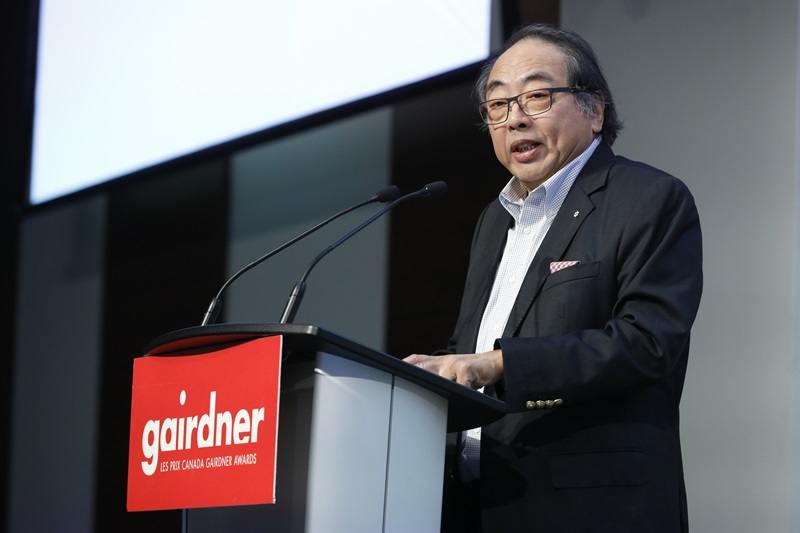

In this post, I’ll highlight some of the key takeaways from the Coming Soon – The Future Of Gene Editing And Gene Therapies panel. This panel was presented by Genome Canada, with Dr. Rob Annan (Genome Canada’s President and CEO) as the moderator. (Panel recordings can be found here in English and French.)

“This topic is certainly close to our hearts at Genome Canada, so we’re really excited to take part and listen to the great experts we have lined up for the discussion,” said Annan in his opening remarks, and then asked panelists to share what considerations need to be kept in mind when it comes to germline editing i.e., genetic changes which can be passed on to future generations.

“At this point, all the indications are that the way we can do gene editing today [that] although it might work for somatic gene editing for diseases, where you’re just treating cells in a person, the risks of doing that in an early embryo and any things that go wrong would be carried forward to the rest of that baby’s life. It’s not safe and precise enough, and it’s not clear that this is really practical at the current time,” said Dr. Janet Rossant, who is the Gairdner Foundations’ current President and Scientific Director, and also served on the expert panel which informed the CCA report. “This just illustrates that when you’re stepping into these areas of complex technologies and complex ethical implications, you have to not just look at what’s happening today, but you have to put yourself in the future and try to think down the line what the future is going to look like and start to have conversations now on how we would deal with those ethical issues coming down the line.”

Different countries will choose to regulate access to gene therapies differently, which may give rise to medical tourism. R. Alta Charo (J.D.), who is a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin, remarked that when it comes to embryonic stem cell research and therapies over the past 25 years, “we’ve had a number of jurisdictions who became famous for basically allowing people to sell snake oil. I think that in both germline and somatic editing, we are going to run the same risk of snake oil clinics.” Charo also noted that for most of the world, one of the more important applications of gene editing will be in the agricultural sector, such as editing plant genomes to adapt to climate change and provide a sustainable food supply.

Dr. Eric Meslin, who is the President and CEO of CCA, took a retrospective perspective, and remarked: “How much of this have we heard about or thought about before? Are there some lessons in the past that we should try to not only remember but actually try to learn from?” Meslin said that “we don’t have to start from scratch” as there are many case examples to turn to, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), and that “there is uneven development and diffusion of these technologies across the global north and the global south”, flagging that there are broader issues of unequal access and care to consider too.

Moving to a communications angle, Jay Ingram, the former co-host of CBC’s Quirks and Quarks, and its TV counterpart, Discovery Channel Canada’s Daily Planet, remarked that “I think what’s really important as we go along is to think: how do we better prepare the communications at every level, country to country, medical expert to politician, CEO to patients […] to be a lot better at it?”

Dr. Vardit Ravitsky, an Associate Professor at the Université de Montréal, flagged two broader issues to keep in mind when it comes to the ethics of genetic research.

“One is the issue of research burden. Where do we do this research?” said Ravitsky. “To edit eggs and embryos, we need egg donors. We need access to ova. That is often an overlooked issue because the places where we go to get this precious resource is sometimes low-income countries, where women ‘donate’ for money. Are they protected locally by research ethic guidelines where they are, in their nations? That’s a huge global issue of justice that is way ahead of the therapies we’re hoping to achieve. It’s about the burden of the research itself. […] Here, in Canada, we banned this research completely, which on one hand, protects egg donors, but on the other hand, may cause reproductive tourism in the future.”

A second issue is that of justice in relation to future generations. Ravitsky said that “the issue becomes: how do we follow up with those that we have created with the technology, to be sure that they’re in good health? First of all, [we need to] just take into account that we’re experimenting on future generations, and second of all, develop mechanisms for including these future generations in follow-up longitudinal research, but without coercing them to remain our research participants.”

To end the panel, Annan asked: “When you turn your eyes to the year 2030, where do you see us going for gene editing?”

Panelists had different suggestions, with Charo predicting that there would be development in the areas of epigenetic editing and in utero somatic editing. Ravitsky predicted that given the lack of international regulatory frameworks, “we will actually have a small cohort of genetically edited babies within ten years that we will have to study.”

“Whenever I’m asked to predict what was going to happen ten years ahead, I always say that I have no idea because if I stepped ten years back, and asked what would we be doing in 2020, just in the area of gene therapy and gene editing alone, let alone more broad-based issues around pandemics and everything else, I would never have predicted where we are today,” said Rossant. “I do think that we are on a very strong and fast path to see real developments of gene editing and gene therapies that are going to have some impact on some major diseases.”

Recordings from the Breaking Through: Delivering On The Promise Of Gene Therapy symposium can be found on the CCA’s YouTube channel.

-min-(1).tmb-cfthumb_fb.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=ef561fc0_1)